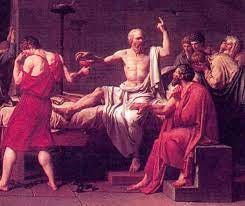

Nietzsche interpreted Socrates’ last words negatively. He claimed that Socrates was an intelligent exemplar of the wrong type of man.

In all ages the wisest have always agreed in their judgment of life: it is no good. At all times and places the same words have been on their lips,—words full of doubt, full of melancholy, full of weariness of life, full of hostility to life. Even Socrates’ dying words were:—‘To live—means to be ill a long while: I owe a cock to the god Æsculapius.’ Even Socrates had had enough of it. What does that prove? What does it point to? Formerly people would have said (—oh, it has been said, and loudly enough too; by our Pessimists loudest of all!): ‘In any case there must be some truth in this! The consensus sapientium is a proof of truth.’—Shall we say the same to-day? May we do so? ‘In any case there must be some sickness here,’ we make reply. These great sages of all periods should first be examined more closely! Is it possible that they were, every one of them, a little shaky on their legs, effete, rocky, decadent? Does wisdom perhaps appear on earth after the manner of a crow attracted by a slight smell of carrion? (Problem of Socrates, #1)[1]

There have been numerous explanations of Socrates’ last words, and I will make a note of them after I have gone through my own.

The Basic Facts to Be Remembered:

Since Plato obscures the basic facts of Socrates’ death it is important we lay them out clearly. Socrates was 72 years old and was committing suicide. Socrates not only thought it important to abide by the decision of the Athenians, but he sought out the death penalty for himself. Xenophon says this explicitly while Plato makes it clear enough.

Asclepius would only heal men who could return to their accustomed way of life. If a man’s illness was going to prevent him from doing what he ought to be doing, Asclepius would not help him stay alive. He did not think a healer should prolong a life of suffering; living should be done for the sake of the accustomed way. Socrates talks about this in book 3 of the Republic.

If we put these two sets of facts together, it becomes clear that Socrates was not thanking Asclepius for healing him of life itself, but from a life that could no longer be good. Socrates was committing suicide because he could no longer live in his accustomed way, philosophizing. He was not committing suicide because life itself is a disease.

I think the only way to save Nietzsche’s account is to say that, according to Socrates, philosophy is a medicine used to counter the disease of life and, not being able to practice the art of philosophy, Socrates decided the disease of life was too much to bear. I am loath even to mention this possible interpretation because of how easily a misguided person could latch onto it and how tedious it is to refute. If you’re led in that direction there isn’t much I can do in an essay anyway. For now: the riddle of life is not a disease and the solution to it not a medicine.

Other Interpretations.

There are a great variety of interpretations out there. Discussing the various inventions of each goes beyond the scope of an essay. There are two I wish to address. There is one that, like mine, is very straightforward and there is another that I like but think is muddled.

Colin Wells claims that Socrates popped his head out because he had not been allowed to pour a libation and had settled on a cock to Asclepius as the next best thing.

“This lingering misgiving [about not being allowed to pour a libation] prompts the request to sacrifice a cock, which we may readily see perfectly meets the deficit. Crito’s promise to wipe out the debt of the unpoured libation, then, allows Socrates to die in peace. His ‘removal’ now has the best chance he can give it of being ‘prosperous.’ Healing, we’ll observe, doesn’t enter into it. If Socrates were a New Age guru, this is where he’d tell Nietzsche that it’s not about the destination, it’s about the journey.” (Wells 143)

Wells’ view is that Socrates was a conventionally pious man who was suffering an unjust execution. He merely wants to enter the next life as reverentially and obediently as possible and he pops his head out because he had been fretting over not being able to libate the gods. Nietzsche is wrong to interpret this request as a rejection of life because Socrates is being killed against his will. Socrates doesn’t think he’s being healed of life; he just doesn’t want to die in disfavor.

The problem with Wells’ view is that Socrates brought the hemlock upon himself. The only real question permitted by the evidence is “why did Socrates do this?” Even if Socrates were only asking Asclepius for some help in making the journey, the question “why” would still remain and Nietzsche could still get his dig in.

Nietzsche could say, “sure, Socrates was only asking Asclepius for some help in passing. But Socrates wanted to make the passing, and he viewed the passing from life to death as if it were a medical procedure, as if life needed this medicine.”

It is only when we remember Socrates’ own view of Asclepius’ art that he can be defended from Nietzsche’s accusation. Socrates sought out death, and when he was dying he thanked Asclepius for saving him—not from life, but from a wretched life, from a life without philosophy.

The second interpretation I want to discuss is that of Ronna Burger, whose view I assumed I would share. She believes that there is a double significance available in Socrates’ command to Crito:

Socrates manifests this recovery when the numbness reaches the organ of generation. He addresses to Crito at this moment his last words: ‘To Asclepius we owe a cock, but pay it and do not neglect it.’ Socrates marks his success in the practice of dying by remembering the god of healing; he believes it necessary, apparently, to supplement the hymn to Apollo he claims to have produced as a rite of purification. Asclepius should be a model for the best physician, Socrates argues on one occasion, since he was willing to heal those who could recover and lead a normal life, but not those who would go on living only with suffering or with constant pampering. Socrates contrasts his own view, however, with that of Pindar and the tragedians, who affirm that Asclepius, though a son of Apollo, was bribed by gold to heal a man already at the point of death. Asclepius, whom Socrates now thinks of in his last words, seems, then, to have a double significance. Does Socrates express his gratitude to the healing god, who knows when it is no longer worth living, for his own recovery from the disease of life? Or does Socrates, who announced his call of fate ‘as a tragic man would say,’ offer at the last moment a bribe to the healing god to fight off the approach of death-one last affirmation of the goodness of life? (216)

If Dr. Burger had stopped before the sentence I put in bold, I would have concluded that I agree with her. But neither of the two options she lists at the end can be right by my reckoning.

Socrates does not think he needs to “recover from the disease of life” nor is he trying to “bribe the healing god to fight off the approach of death.”

Rather than either of these options, what I say is true above is what Dr. Burger seems to have been saying above when she says, Asclepius “was willing to heal those who could recover and lead a normal life, but not those who would go on living only with suffering or with constant pampering.”

“We” not “I”

When Nietzsche quotes Socrates, he quotes him saying “I owe a cock to Asclepius,” but Socrates says “we,” not “I.” HerodoteanDreams suggests that this is because Socrates is giving a teaching about life and the afterlife, an ascetic morality, wherein he groups himself with his frankly unmanly listeners. His message throughout the Phaedo, on this reading, is a statement of what would be good “for all”—we—rather than what is genuinely true for himself. And that perhaps Nietzsche displayed his own awareness of this by misquoting him, insofar as it is doubtful he overlooked this or mistranslated the Greek.

Leading a Way of Life.

In the Republic, where Socrates discusses the art of Asclepius, he speaks of craftsmen or laborers—of men who have to work for their living. The point he makes is that one of these will not willingly spend all their time trying to simply stay alive. They can’t sit around applying medicines; they have to get back to work. There was another healer, Herodicus, who taught men how to nurse themselves into a longer life, but whose every waking moment could focus on nothing else but nursing their illness.

Socrates mentions the men who need to work for their bread. If you think about it, the workers do not seem to be in a much greater position than the men whose illness keeps them focused on it to the exclusion of anything else noble or good. Of course, in this way Socrates affirms “mere life” of a kind—the working kind—while denigrating mere life of another kind, the sickly kind.

And behind it all is his own life and his own way. Like the workers, Socrates won’t be parted from his way; but unlike them, his way is not undertaken for any of the necessities, nor even for the typically grand things like political office. He’s not even doing it for sex! Socrates philosophizes for the sake of his life, of motion and his own awareness of his own motion—and his awareness of that awareness.

[1] See also the Gay Science (#340).

This is a lovely essay.